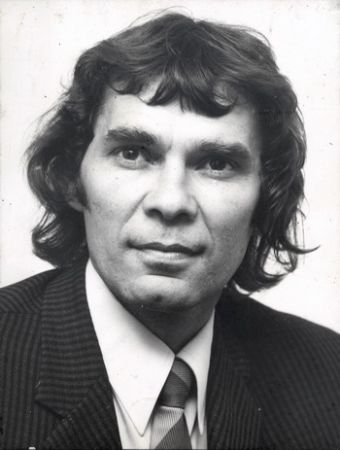

Gordon Briscoe

(1938 to 2023)

Source: Northern Territory Library and Information Service

Gordon Briscoe was taken from his Marduntjara mother as a boy and educated at St Francis House in Adelaide. Together with Charles Perkins, Vince Copley, John Moriarty and Don Dunstan, he campaigned to get racially discriminatory legislation repealed in South Australia.

Gordon attended Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) meetings in Canberra in the 1960s and, in the 1970s, worked in the newly established Department of Aboriginal Affairs. He helped establish the Aboriginal Medical Centre in Redfern in 1969 and later worked with Fred Hollows on the National Trachoma Project.

Gordon pursued a second career as an academic at the Australian National University in Canberra. His PhD research was published as Counting, Health and Identity: A History of Aboriginal Health and Demography in Western Australia and Queensland, 1900-1940 (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2003). He has also worked and published with Dr Len Smith of the Australian National University with whom he has compiled population figures of Aboriginal people.

In a 1996 interview he reflected on the tensions, views and strong emotions which Indigenous people brought to FCAATSI conferences.

These sorts of people [Doug Nicholls, and Bill and Eric Onus] were, if you like, the old hands, teaching the young people how to articulate in public meetings and encouraging them to speak up and tell other groups in Australia what it was like to live in Victoria, under the Welfare Board influences, what it was like to grow up in Fitzroy. What it was like to be sort of shadowed by the coppers, to be suspect all the time because you were an Aborigine, never to be praised in the society you believed that, that you had a much greater role to play in, than you were allowed to play. So there were all these pent up problems that the young people could feel: the crowding in of prejudice, the question of not being able to do what white people did, not having the freedom to be able to get rolling drunk, and you know getting chucked out of the pubs and this sort of thing, where white fellas would still be inside, in the same condition. So [an awareness of] racial prejudice was something that I felt people brought to FCAATSI. They brought a very hostile feeling, that of rejection by whites, of being definitely second class citizens, and being made to feel second class citizens because of their inherent poverty; the inability of the Welfare Board to see their basic needs and rights as landlords of the properties they lived in; the levels of rent that the Welfare Board set; the parsimonious nature of the State Welfare Board system.

Gordon analysed some Indigenous responses to political strategy. What did people want? How should goals be pursued?

Ken Brindle was an ex-military man, and he was a sort of promoter of Aboriginal workers, and Christian ideologies in New South Wales. He had a better feel for New South Wales than Charlie Perkins did. But Charlie Perkins was a sort of pretty boy, in the sense that he was always well dressed, he was always well spoken, and the other people were more or less antagonistic towards him because he represented a sort of an upper class view rather than the fringe camp mentality of the Brindles or the inner city mentality of the Christian groups who looked to things like employment, racial prejudice in Newtown by police. Charlie was not all that interested in those sorts of things. He believed that they look after themselves, whereas he wanted to bring down the welfare structure. He was anti welfare. He didn't want Aborigines coming to represent their people, asking for food, asking for rent, all these things. Charlie was an individualist, a sort of a Liberal, who believed that if you had the opportunity you could do anything you wanted to do. Whereas Brindle had the idea that the state had to be there and had to be doing, had responsibilities towards Aborigines, whereas Charlie felt that all these things you could do for yourself. So it was a class based structure. The differences were class based and, of course, Joe was the appeaser. He wanted national organisation and would, like Doug Nicholls, (Joe McGinness from Queensland that is, not Joe McGuinness from Melbourne). But Joe McGinness was a cooperator, with everyone and sundry that wanted to push the idea that Aboriginal organisations had to have a national body and FCAATSI was it, or FCAA first, and then FCAATSI as it became, because most populations in Australia didn't have a Torres Strait Island group. They only had the one Aboriginal group except that it was broken up into sort of ethnicity or regional conflict groups, right? So, for example, the southern Riverina blacks always had differences of opinion about how and what to do about Aboriginal affairs and lived fairly close to one another. They were the old urban structures, urban groups, whereas the new ones were like the northern rivers people starting to migrate down into Sydney in the mid '60s. The Act really wasn't working in New South Wales, so people were starting to leave reserves and move to the city and get jobs. So there was this group of people there with different ethnic factions, different beliefs. Some had just come directly from reserves, whereas other people had been in the army and gone away and come back and so forth. And then there was Charlie Perkins who was the sort of slick, articulate kid who had the churches in his hand - the big churches, not the little evangelical churches, but the big churches.

The most important person in FCAATSI was Doug [Nicholls]. I mean I think Joe felt that he was as important as Doug. Doug had the Church behind him and Joe always felt that he was more important than Doug, because Joe was a unionist in Queensland and he had the ear of the left wing unionists, whereas Doug, Doug was a liberal. He had sort of access to the upper crust in Melbourne. He could give a sermon in any one of the churches in Melbourne and be listened to. He could rally people - Aborigines in Victoria - like no-one else could. And that's where FCAATSI started. It started in Victoria. It got the support of Queenslanders ultimately, but it was Victoria where FCAATSI started, and it was through the Church and the Aborigines Advancement League. It had the notion of cooperating with people.

He drew attention to the important role played by the Communist Party of Australia in the movement for Aboriginal rights.

Oh I think you can't really understand the growth and development of Aboriginal politics in any way, unless you can understand the role that the trade union and the left played in developing - firstly looking at Aboriginal poverty as an abhorrent thing; looking at the legislations under which Aborigines lived; looking at democracy as a way of articulating people's despair and poverty - without understanding that it was the Communists who went to the Russian presidium, the big Communist conference in 1921. It certainly set off the German revolution, that's one claim to fame of that conference. It was presided over by Lenin and a number of Communists from Australia were there and they came back buoyed up, looking for their poor. And they found it in Aborigines - 1925, when the first article was written by the Communist Party about the poverty and despair of Aborigines: the way that white society had neglected them; the way that Aborigines had no rights and were treated like outcasts in Australia. I mean obviously there are, as Jack Horner would argue, earlier roots of unionism and Aborigines, and that's true. But it wasn't urban based. It was rural based. The urban based radicalism began in Sydney. It took something like fifteen years for them to get a group of Aborigines out on the streets, saying something in a peaceful way about their despair. About the way they wanted acceptance and inclusion, rather than exclusion.

Source: The extracts on this page are from an interview with Gordon Briscoe conducted by Sue Taffe on 5 December 1996

Further reading

Gordon Briscoe, Indigenous Australians, from Gordon Briscoe, Racial Folly: A Twentieth Century Aboriginal Family, ANU ePress and Aboriginal History Inc., Canberra, 2010

384354

- 391528

- 391534

- 382876

- 383008

- 383424

- 391546

- 382776

- 382880

- 391556

- 391562

- 391568

- 391580

- 391574

- 391586

- 384354

- 383635

- 391596

- 382884

- 383268

- 383959

- 383044

- 391608

- 391614

- 384358

- 383256

- 391624

- 382964

- 391680

- 391686

- 383658

- 382888

- 391696

- 383260

- 382780

- 391706

- 384213

- 383837

- 383264

- 391718

- 383841

- 382968

- 391728

- 383704

- 383012

- 382748

- 382892

- 383570

- 383316

- 391748

- 383048

- 383754

- 383666

- 383104

- 391763

- 383662

- 384061

- 384065

- 391774

- 391780

- 391785

- 383188

- 383708

- 391795

- 391801

- 391807

- 383336

- 384362

- 382856

- 383272

- 383963

- 391819

- 382896

- 391825

- 382972

- 383296

- 383080

- 383758

- 383108

- 384069

- 391851

- 391857

- 391863

- 391869

- 382900

- 384366

- 382784

- 391882

- 391888

- 382904

- 383712

- 391900

- 383084

- 391908