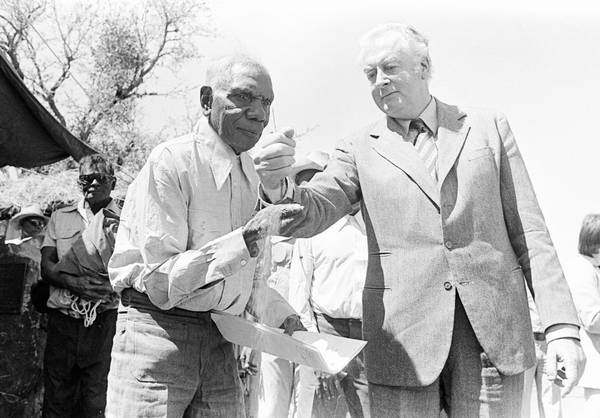

On 26 August 1975 Prime Minister Gough Whitlam handed a leasehold title to land at Daguragu (Wattie Creek) to Vincent Lingiari, representative of the Gurindji people.

Source: National Archives of Australia, Canberra

A long and little recognised struggle

The Aboriginal struggle to regain lands taken from them has a long history. Since 1846 when Aboriginal Tasmanians petitioned Queen Victoria, Indigenous people have been using the laws and the parliamentary system of government brought by the British in their attempts to regain land.

Early voices

In the south-east of the continent, where people had been pushed onto 'reserves' or 'missions' and then moved from one mission station to another, Aboriginal voices expressed outrage and grievance:

Shadrach James, 1930:

We are the descendants of the people you have unjustly disinherited of their land. We are at present - shame on the Governments of this land - landless and homeless wanderers. [1]

William Cooper, 1933, from 'Petition to the King':

It was not only a moral duty, but also a strict injunction included in the commission issued to those who came to people Australia that the original occupants and we, their heirs and successors, should be adequately cared for. Instead, our lands have been expropriated. [2]

Mary Clarke, 1951, speaking of Framlingham in Victoria:

The white people never thought of paying US rent for the whole country that they took from our ancestors. Leave us this tiny corner where our homes are. Why should we pay rent for it at all? We regard that little bit of land as ours still. [3]

A challenge to the Australian state

Campaigns for civil rights saw Indigenous Australians, who were technically citizens, though deprived of rights by state laws, being given access to the laws which protected the rights of settler Australians.

Campaigns for land were fundamentally different, in that they questioned the very process by which the continent was settled, and which, in that process, dispossessed the original land holders.

As Henry Reynolds reminds us:

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, the law continued to insist that Australia was uninhabited, that no-one was in possession. Various jurists described the country as being 'waste and uninhabited', 'waste and unoccupied', 'desert and uninhabited', 'unpeopled'. [4]

And yet, in English law, as Reynolds notes, possession was always considered to be nine-tenths of the law. Why did this not apply to the people in possession when Europeans arrived?

Unlike the campaigns for civil rights, the land rights issue challenged the very basis of the Australian state.

The emergence of a national land rights movement

When bauxite was discovered on Aboriginal reserve land on Cape York Peninsula and Arnhem Land in Far North Queensland and the Northern Territory, the issue became a matter for national public debate. Did governments have the right to compulsorily move people from these reserves? Petitions and campaigns put the case for the creation of an Indigenous title to land.

Footnotes

1 Shadrach L James, 'Help my people', 24 March 1930, in Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights, Sydney 1999, p. 142.

2 William Cooper, 'Petition to the King', The Herald, 15 September 1933, in Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights, Sydney, 1999, p. 144.

3 'Leave us a tiny corner native plea', Argus, 22 February 1951.

4 Henry Reynolds, The Law of the Land, second edition, Penguin, Ringwood, Victoria, 1992, p. 3. This book is highly recommended for those wishing to understand the legal and moral arguments for an Aboriginal title to land. The second edition was written after the historic High Court Mabo judgement and includes a postscript which discusses this case.