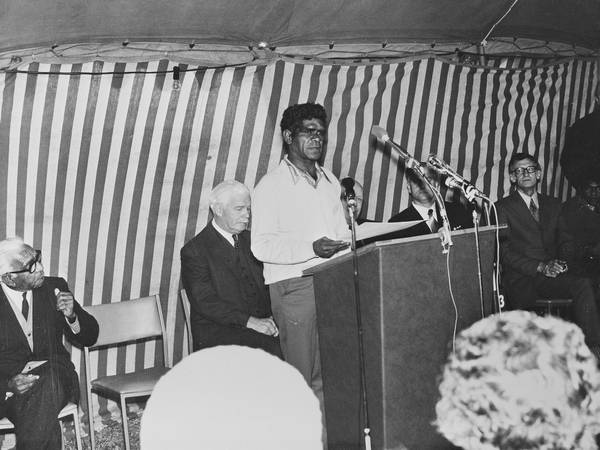

Charlie Carter receives the title deed to Lake Tyers on behalf of residents. Rohan Delacombe, Governor of Victoria, is to his right. Pastor Doug Nicholls, far left, looks on.

Source: Audio Visual Archive, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra

Fighting to save an Aboriginal reserve

In 1957, the Victorian government accepted the recommendations of a report it had commissioned into Aboriginal affairs. Named after its principal author, retired Chief Stipendiary Magistrate Charles McLean, the McLean Report argued that Lake Tyers in south-eastern Victoria should be closed down, and that such an action would hasten the assimilation of Aboriginal Victorians into the mainstream community.

The government promised better quality houses as an inducement for people to leave Lake Tyers. The major drawback was that the houses were scattered around country towns and often a long way from home. Colin Tatz, a member of the Victorian Aborigines Welfare Board, disparagingly referred to this strategy as 'pepper potting'. The cost was high for those who moved - social isolation from friends and relatives. And once they left Lake Tyers, they were not permitted to return.

Lake Tyers was the only remaining Victorian reserve for Aboriginal people which was staffed. The fight to save it was supported by churches, unions and activist organisations, and the protest grew until it could not be ignored. This was a clash of ideas: assimilation of the Lake Tyers population into the mainstream community, or recognition that people had a right to stay on the Lake Tyers reserve - on land which was their home.