Decision to close Lake Tyers

The McLean Report

In 1953 Charles McLean, a recently retired Chief Stipendiary Magistrate, was appointed to enquire into the operation of the Aborigines Act 1928. His report, tabled in 1957, suggested a policy of 'active assimilation' as the basis for Victorian policy in Aboriginal affairs over the next decade. [1] One of the specific matters he was asked to report on was the question of whether the Lake Tyers Aboriginal station should be retained or discontinued. [2]

McLean argued that Lake Tyers should be kept, but only for those who were old and infirm, and he recommended that the size of the reserve be reduced. His policy of active assimilation recommended that housing be offered in country towns but that no more than two or three families be allowed to settle in the same town.

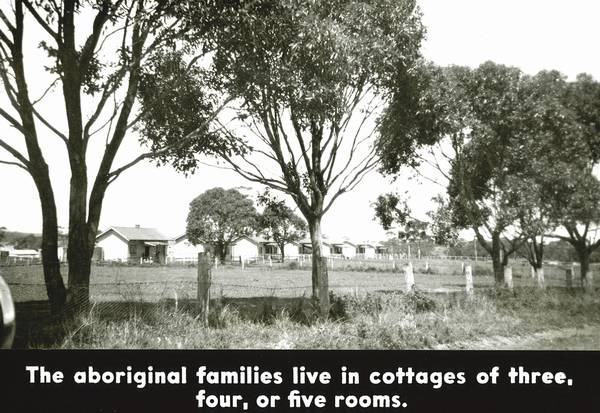

The caption on the image reads: 'The aboriginal families live in cottages of three, four, or five rooms'.

Source: Reproduced with the permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office of Victoria, PROV 14562/P4/6

Only primary level education was offered at Lake Tyers.

Source: Reproduced with the permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office of Victoria, PROV 14514/P1/25

Council for Aboriginal Rights report

In December 1961, at the suggestion of Laurie Moffatt from Lake Tyers, a Council for Aboriginal Rights delegation visited Lake Tyers Reserve to see conditions on the reserve for themselves.

The delegation reported that the homes of the 150 people living there were without running water and without a drainage system. The community bath house was hundreds of yards away from some homes. As a consequence of insanitary conditions, most of the children on the reserve suffered from intestinal worms, and pneumonia was frequent. Residents, however, could only consult the doctor who visited the settlement once a month, if the manager's wife approved such a consultation. The people depended on rations, which they collected from the store twice a week.

Council for Aboriginal Rights report on Lake Tyers, 1961

Council for Aboriginal Rights, MS 12913/7, State Library of Victoria

More info on Council for Aboriginal Rights report on Lake Tyers, 1961

The gate to the reserve was locked and if residents left the reserve without permission they were fined. If people entered the reserve without permission they were summonsed for trespass. It was against government regulations for residents to own a car, so if they wanted to go into town at Lakes Entrance they walked the 25 kilometres to get there. The people worked under supervision. The only schooling on the reserve was a primary school. The approach was paternalistic and the people were demoralised.

Residents request permission to leave Lake Tyers to march in support of the settlement

National Archives of Australia, Melbourne

More info on Residents request permission to leave Lake Tyers to march in support of the settlement

Government decides to close the reserve

In 1962 the Victorian Chief Secretary announced that, following the recommendation of the McLean Report, Lake Tyers would be abolished. He claimed that the 'worst service to Aboriginal families would be to continue to improve Lake Tyers'. [3]

Many people living at Lake Tyers had been there for generations. Some were Gunnai people, the original inhabitants of the region. Others had come from different parts of the state when other missions and reserves were progressively closed down. By 1962, Lake Tyers was the only government-supervised Aboriginal reserve in Victoria.

Opposing views on the closure

Two diametrically opposed views emerged: the Victorian government held that residents could only gain equal rights and treatment if they lived and worked among white people. Thus, Lake Tyers residents were under heavy pressure to move to country towns which, in some cases, were hundreds of kilometres away from family and friends.

An opposing view saw this as coercive assimilation. Lake Tyers residents had not been prepared, practically or emotionally, for this radical change in their lives. And besides, it was argued, they should be able to continue living at Lake Tyers if they wished to do so. Moreover, those opposing coercive assimilation argued that Aboriginal residents of Lake Tyers and Framlingham, the only other Victorian reserve (it was not staffed), should be entitled, legally and morally, to ownership of these remaining reserve lands.

Others, such as anthropologist Dr Diane Barwick, who made a personal submission to the Victorian Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, referred to policy in other countries and argued for people's right to be consulted on social policy. She also criticised the Aborigines Welfare Board for refusing to allow seasonal workers who had left the reserve to return.

'Lake Tyers Reserve: an anthropologist's submission', Dr Diane Barwick

Smoke Signals, April-June 1965

More info on 'Lake Tyers Reserve: an anthropologist's submission', Dr Diane Barwick

A failed exercise in social engineering

Some families were persuaded to move from Lake Tyers with offers of houses, but they had not been prepared for the move. They had no experience in handling their own money, in living in a house with power, water and sewerage connected, and in working or mixing socially with a white community.

Once residents left Lake Tyers they were not allowed to return. Many were unhappy and tried to return to Lake Tyers, but permission was refused. By 1966, less than half of the Aboriginal families rehoused by the Aboriginal Welfare Board were still in the houses provided. [4]

Related resources

Footnotes

1 The McLean Report, Parliamentary Papers (Victoria), 1956-58, vol 2, paper no 14.

2 Aboriginal reserves that had government staff were often called 'stations'.

3 Melbourne Herald, 16 April 1962.

4 By the 1960s, the Board for the Protection of Aborigines had changed its name to the Aborigines Welfare Board.

383925

- 383896

- 383925

- 383971

- 384025

- 384034