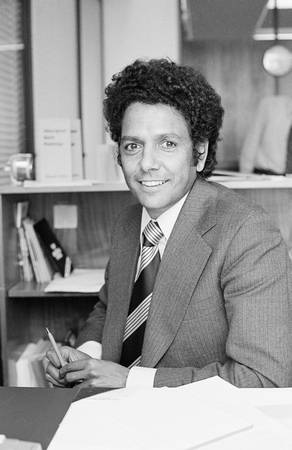

John Moriarty

(1938)

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A8739, A8/8/74/15

John Moriarty, of Yanuwa descent, was taken from his mother at Borroloola south-east of Darwin without her consent when he was five years old. They did not see each other for the next 10 years. After living in a number of institutions he was educated by Father Percy Smith at St Francis' Anglican Home in Adelaide. Here he met Gordon Briscoe, Charles Perkins, Malcolm Cooper, Vince Copley and other young Aboriginal men who would play active roles in fighting for their people from the late 1950s onwards. He represented both his state and his country playing soccer at home and abroad.

I think there were some of us that were taken away from our parents, like Wally McArthur, Jim Foster, (I'm not sure about Harry Russell, but I believe he was) myself, Wilf Huddlestone, Tim Campbell, we were all taken away. But people like Charlie Perkins, Malcolm Cooper, Bill Espie and all those early boys, were there because their mothers had requested them to be placed, first of all at that home or that hostel in Alice Springs, which was almost like a school boarding house, you know like the pastoralists that were coming in. In fact it was shared with a lot of pastoralists' children when Father Smith started that place up there. But when he started in Adelaide the boys from the top end of the Territory like those ones that were taken away were put in that home as well. And from that first twenty-three boys, when I was there, when I first moved to St Francis House, one - two - three of us have university degrees, about eight of us had trades, one - two - three - four - five - six - seven, about eight of us represented our state in particular sports, Wally McArthur and Jim Foster went over to England to play rugby and they played top class rugby, and Gordon Briscoe, Charlie Perkins and I went over to England to play soccer. I didn't end up playing soccer, but I was called back here and that's when I went to university, and I represented South Australia, was chosen for the Australian team here, but I suppose for a boys' - and Aboriginal boys' - home, it was quite exceptional for the time. And people like Malcolm Cooper was - who died very young in my view with a brain haemorrhage, while he was in Tennant Creek, he was flown up to Darwin, you know, he died before he got to Darwin - had a great deal of potential too to go on.

Sue: What age was he when he died?

John: Oh I think he was in his twenties or thirties, early, maybe early thirties. But Malcolm had a lot going for him too, and he was a good footballer. He played for Port Adelaide. But St Francis House was an exceptional home. If you look at the situation today and look back in retrospect. But FCAATSI, with the fight for the referendum, FCAATSI had a very concerted program that was done nationally. Joe McGinness, because he was president of FCAATSI, he was living in Cairns at the time, he was with the Waterside Workers' Federation, and he travelled to all the capital cities: part of his program to fight for the referendum, for a yes vote.

Sue: So he came to Adelaide?

John: He came to Adelaide, and we had quite a few meetings. And we always got good press in Adelaide at that time. And apparently we were saying all the right things to get the press because it was very radical stuff in those days. And Joe played a very strong role in that. And people like Stan Davey had a coordinating role as secretary of FCAATSI, but he was also very involved with the Aborigines Advancement League in Victoria. And then he moved up to Western Australia. I think his marriage broke up and he moved on.

In 1960 I was selected to play my first state game for South Australia, to play in Western Australia - this is in soccer. We travelled to Western Australia and the chairman of the South Australian Soccer Federation had to seek permission from the Protector of Aborigines, who was Mr Bartlett at the time, located in Kintore Avenue in Adelaide, to seek permission for me to travel outside Adelaide to represent South Australia in sport. I didn't know about this until much, much later.

Sue: You didn't know that that had to happen?

John: I did not know that that was part of the system of law that had to be adhered to before I could travel interstate representing all South Australians in my sport. And I disliked that intensely when I found out, and I started to jack up as a matter of principle. Then I started fighting for Aboriginal rights, you know, that much harder. And I remember meeting my mother for the first time after an absence of ten years because I was one of those that was taken away from my mother, my mother's a tribal Aboriginal woman. In the old days they used to call them full bloods and me with an Irish father was called a half caste, so half caste kids as was called in those days were taken away from their, their full blood parent. And I was taken from Roper River Mission down through Adelaide via Alice Springs, on to Sydney and from Sydney out to west of Sydney, a place called Mullagalah which is forty miles west.

Sue: How old were you, John, then?

John: I was about five, maybe six. Yeah, no about five I think. And I travelled with that group of Aboriginal people, men, women and children, I was one of the younger ones, and we were a little enclave over there that - the thing that I didn't like was that when I met my mother again in 1953, after a ten year absence, and I had to chase her myself through friends, and it was one of those situations, which is pretty trying for me to meet up again and we just happened to meet in the street, and we chatted and talked and then my mother was considered a ward of the state, and she was an adult, and I was a fifteen-year-old boy, just at high school and we met, and then she had to go back. She had to do what she was told because she was a ward. She was sent from one spot to another. That was the power of the government and the welfare system that Aborigines had to live and work and die by. So I was one of those that took up the cause and I think soccer was one of those very important aspects of my life, which enabled me [to] develop a profile and be treated as a normal person. So that the influx of Europeans, Italians, Greeks and those from eastern Europe, came here and they were all soccer mad, and I felt more at ease with these people playing soccer and mixing with them, than I did with what I'd term the colonial Australian people.

Aborigines in those days were people that, under [the Act] unless you had an exemption, were always an Aborigine. So if you got an exemption you could just walk through the - participate in white life in those days, but I refused to, in fact I was asked whether I wanted an exemption, because I was seen as a model Aboriginal, had done a trade and was playing, or was doing a trade at the time, and I turned twenty-one and I had completed my trade by then and someone says would you like an exemption and I said 'not on your life'. I said 'I refuse to have one', because my principles wouldn't allow me to say that I have obtained the standard of living equal to that of a white man, and be treated as such from now on. In other words I would have been a black white man. And I refused all that. And this made me much more determined to fight for Aboriginal rights.

John Moriarty was a foundation member of South Australia's Aborigines' Progress Association.

I think the establishment of the Aborigines' Progress Association - that was established after Laurie Bryan had left the Advancement League and Malcolm Cooper was also with the Advancement League, I'm sure he was, and he'd left there, and Malcolm asked me to join with him in setting up the Progress Association. Winnie Branson was another member of course, and Bert Clarke and we just continued developing. I think I was - what was I - vice president to begin with and Malcolm Cooper as president, and I was very happy with Malcolm being president. He was older than me and I respected him and he had a home, one of those government South Australian Housing Trust homes, at 5 Talbot Street, Angle Park, and we used to meet there at his place and another lady, Winnie Branson's sister, yes, Mary Williams. We used to call her Auntie Mary. She was a fiery sort of a lady too, and Auntie Mary was very strong on the injustices of Aborigines. She had a hot temper, but with me she was - we got on very well. But with Malcolm Cooper, it was like rubbing a match against a striker, you know it will flare up in no time flat. So poor old Malcolm used to get so frustrated with her, and she knew how to get Malcolm off side, but that was really the foundation of the Aborigines' Progress Association.

Sue: That was a different sort of organisation to the Aborigines Advancement League here?

John: Very different to the Advancement League. It was a body that began fighting on the political front. So we set about for land rights, with the Lands Trust Act. We had a lot of Aborigines were alcoholics, you know. We pulled all those people in, we set up a football team, and things like that, we set up dances. We set up the Aboriginal Legal Service, the basis of it, and even one of those very early meetings in Port Adelaide we took Elliot Johnston down there, and Elliot Johnston still refers to that meeting as one of his baptisms into the Aboriginal affairs legal issues. [Elliot Johnston later played an important role in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1988, 1989]. I addressed that meeting council there and he got a lot out of that meeting, which really brought out with him his views on Aboriginals and the legal system, so when Gordon Bryant was Minister, you know, legal services were being established from Commonwealth funding, and the body was established here as well. And Vince Copley one of our members, and who was our first Director of the Aboriginal Community Centre, said that the Progress Association set it all up through the efforts that I had achieved with getting funding from government sources. But I think the strength of the Progress Association was that it linked in, it was an affiliate organisation of FCAATSI.

There's a fellow called Bert Clarke and Winnie Branson. Winnie Branson was a very strong person. In fact she was one of the persons that had a strong influence on me in those days. She was a tough person, had a lot of vision, and yet she was one of those encouraging types of persons. And Bert Clarke was another. Bert Clarke was an Adnyamathanha person from Nepabunna. He was initiated into the Dieri Wangkangurru tribal groups up there in the North, and he and I were part of the Aborigines' Progress Association, and Malcolm Cooper was another person.

John was a vice-president of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) from 1968 to 1969, playing an active role through the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1973 he took a position in the newly formed Department of Aboriginal Affairs. Here he shares his views of some of the key activists in Aboriginal affairs during these years.

Joe [McGinness] was a true, and still is in my view, statesman for Aboriginal people. We don't look to our elders as we should in my view and I think that's one of the problems in Aboriginal affairs today. If you look at the elders in my tribe, you have forty thousand years' knowledge of the old traditions, the old songs, and the old ceremonies. You know, those things just don't come easy, they take, you know, a full lifetime to assimilate and you must have sufficient intelligence and the wherewithal to become an elder and these are the sorts of people who come to the forefront. Not everyone can be an elder in that sense. But we are not, and we have not, even in those days, maintained that continuity from elders.

But the old leader, Joe McGinness, who was so quietly spoken, was more of a statesman than a speaker. But he was always there, he was rock solid. With his sincerity, Joe got a lot of people on side too.

FCAATSI really had a role, and in those early days very few Aboriginal people were involved. You can count them on your two hands. Evelyn Scott came in early, and people like Faith Bandler, and Kath Walker seem to have always been there, even old Jack Davis, Joe McGinness, of course was there from the beginning, and lots of people like him. We had a few tribal fellows that came in from the Northern Territory once the 1960s meetings in Canberra started to gain their momentum. People like Davis Daniels, Phillip Roberts, Dexter Daniels and those people were supported by the unions and were funded by the unions to come down. Or people like Burnum Burnum is another one, you know (Harry Penrith as he was then), and Bert Groves. Bert Groves was a great fighter from New South Wales and some of those fellows were not given the due recognition they should have been.

I kept very close contact with Dr Duguid and he was a real statesman. In fact, I visited him for years and years, right up until his death. He was one of those persons that had a very strong Aberdeen accent. He was a very strong soccer supporter, and the first thing that we spoke of, because I was very keen on soccer, we'd start off with soccer just to get things moving, then we started talking about all other issues. But it invariably focused on Aboriginal affairs and, while Dr Duguid started that Colebrook Home up in the hills, which was a focus for the Advancement League as well as the Millswood Hostel, they were very practical type of things, and I thought they were not treating the complaint, rather symptoms. And my idea was to get right to the base of the issue, you know, like hitting someone with penicillin rather than putting a bandaid on a sore; hit it with penicillin so that the whole system is rightened.

FCAATSI was fighting on the political front in trying to, well, get federal involvement and take over responsibilities for Aboriginal affairs, which is the whole fight for the referendum. And that was one of the successes, the major successes in my view, that FCAATSI achieved. But before doing that I thought FCAATSI had a huge role to play because it focused Aboriginal attention at a national level through its affiliates, and those affiliates were very powerful bodies in those days: Teachers' federations, the waterside workers in many states and many ports, throughout Australia, different types of unions, even the AWU [Australian Workers Union] was a strong one.

And when we started fighting for the equal wages for Aborigines on properties, we were granted equal wages through that fight that was taken through Monash University conferences when Colin Tatz was involved. I was one of those that was involved in that [a conference on Aborigines and the economy hosted by the Centre for Research into Aboriginal Affairs, Monash University in 1996] and I spoke at those and we got equal wages for Aborigines in 1966, but it wasn't granted until Christmas 1968. [John is referring to the 1966 conciliation and arbitration ruling on Aboriginal pastoral workers]. And that was one of those things that really changed my thinking in Aboriginal affairs many years later.

I'd fought very hard for those equal wages for those people on the properties, because they were my relations up in the Northern Territory. And they were getting rations for this, rations for that, you know, clothing, tobacco, flour, sugar all those things, and very little money and the industry operated just on the backs of Aborigines, because they knew the country, and at that time the wages structure was such that, you know, they could make a very good living out of running cattle in those very expansive type of cattle properties in the outback. But what I thought it would do, it would bring about equality, and it did in one sense, but what the down side was, that it pushed Aborigines off those properties, and they had little claim later for the land area on those properties and that is one of the big regrets that I've had since fighting for those equal wages and part of that strategy. So that was a downside for me in that.

But the FCAATSI organisation enabled Aboriginal people to come and meet over the Easter break. They had to make their own way to those places, and, like I said I was a poor student, during my university days, and we still made the trips over there. In fact all those Aborigines in those times paid their own expenses to fight for the rights of Aborigines, and that same group are still independent minded like that. Unfortunately we can't say the same about the modern Aboriginal mentality. It's more focused and geared towards money, money, give us money from government and other sources. And I think that's one of the downsides of having the referendum fought and getting the federal government to take over responsibilities for all Aborigines.

John recalls some of the key Aboriginal activists in Western Australia.

But it was FCAATSI that set the platform that we were able to spread our wings a lot further, and at that conference Nandjiwara Amagula, a summer school, a relative of mine, an uncle of mine from Groote Eylandt also spoke at that conference. [41st annual summer school, Adult Education and Extension Service, University of Western Australia, 1969.] So that really kicked the Aboriginal affairs issues on in Western Australia, and people like George Abdullah, Jack Davis and a lot of those people, you know, took up the fight, Don Farmer was another one. Prosser, Arthur Prosser, and a lot of these people did. Course Ken Colbung was involved for a long time too in Sydney with the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs. And Ken was also one of those that took the fight up, and he lived in Sydney. He was an ex-army man, but he was initiated in the tribal ways, so, and the bloke's still, you know, a prominent man in Aboriginal affairs. And these are the sort of people that have been very strong, very independent, and they were the ones that really put Aboriginal affairs on the map to what, what it is today really. They set the foundations of what is today.

Sue: It must have been much harder for those people over in the West. I mean, I had the sense that because of distance and because of their lack of funding, it was just much more difficult for them to get across. So they were more isolated and so FCAATSI was more helpful, I suppose, to the East coast and to Adelaide, and even to Northern Territory, than to people in the West.

John: Yes. That's right. Western Australia was a really isolated place and the laws in Western Australia were so horrific, geared against the Aboriginal person, and I recall one of the FCAATSI meetings, we had a delegate from Western Australia, our very first delegate was Fay Kickett, one of the Kickett family and I recall at that Canberra meeting 'we have a delegate from Western Australia, her name is Fay Kickett', and she was brought up on stage and everybody clapped and said right, you know, 'Australia's getting smaller, Aborigines are becoming more involved, we're getting better representation!'

John now works as an artist and is a very successful businessman. His design company Balarinji is responsible for the largest piece of movable Aboriginal art, the Qantas Wunala (Kangaroo) Dreaming 747 aircraft. In 2000 his autobiography, Saltwater Fella, was published, showing John's journeys to connect with both his Irish and his Yanuwa families.

John was awarded an AM in 2000.

Source: The extracts on this page are from an interview with John Moriarty conducted by Sue Taffe on 25-26 November 1996

Further reading

John Moriarty, Saltwater Fella, Viking, Ringwood, 2000

391807

- 391528

- 391534

- 382876

- 383008

- 383424

- 391546

- 382776

- 382880

- 391556

- 391562

- 391568

- 391580

- 391574

- 391586

- 384354

- 383635

- 391596

- 382884

- 383268

- 383959

- 383044

- 391608

- 391614

- 384358

- 383256

- 391624

- 382964

- 391680

- 391686

- 383658

- 382888

- 391696

- 383260

- 382780

- 391706

- 384213

- 383837

- 383264

- 391718

- 383841

- 382968

- 391728

- 383704

- 383012

- 382748

- 382892

- 383570

- 383316

- 391748

- 383048

- 383754

- 383666

- 383104

- 391763

- 383662

- 384061

- 384065

- 391774

- 391780

- 391785

- 383188

- 383708

- 391795

- 391801

- 391807

- 383336

- 384362

- 382856

- 383272

- 383963

- 391819

- 382896

- 391825

- 382972

- 383296

- 383080

- 383758

- 383108

- 384069

- 391851

- 391857

- 391863

- 391869

- 382900

- 384366

- 382784

- 391882

- 391888

- 382904

- 383712

- 391900

- 383084

- 391908