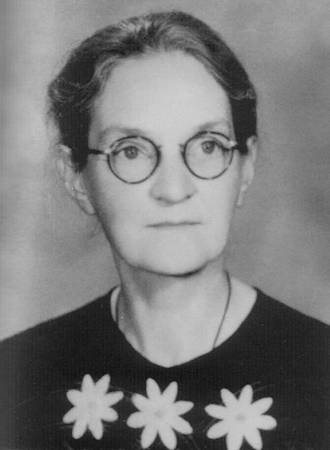

Mary Montgomerie Bennett

(1881 to 1961)

Source: Courtesy Elizabeth Roberts

Mary Montgomerie Bennett had an unusual childhood with a Queensland pastoralist father, Robert Christison, who expressed a deep sympathy for the dispossessed Dalleburra people on his pastoral run. While living in England in the 1920s, Mary went to hear Constance Cooke, a member of the Aborigines' Welfare Committee of the Women's Non-Party Association of South Australia, deliver the annual address to the London Anti-Slavery Society. Hearing this address added to her growing conviction that she should devote the rest of her life to improving conditions for Aboriginal people.

Mary used her contacts in England to publicise sexual abuse of Aboriginal women, forcible removal of children, loss of land (and thus of an economic base) which led, in some cases, to prostitution. Following British press coverage of her charges, a Royal Commissioner, Henry Mosely, was appointed to 'Investigate, Report and Advise upon Matters in relation to the Condition and Treatment of Aborigines'. Mary gave evidence before this Commission in 1924, admonishing the Western Australian government for its policy of separating children from their parents. 'No department in the world', she told the Commission, 'can take the place of a child's mother and the Honorable Minister does not offer any valid justification for the official smashing of native family and community life'.

When her English husband died in 1927 she returned to Australia, settling in Western Australia. She made contact with Ada Bromham who would become a lifelong friend and ally. Mary worked as a teacher at Mount Margaret Mission near Laverton in Western Australia where she taught children the skills they would need to enter the white man's world. In her old age, from her Kalgoorlie home, she assisted the aged and unemployed to apply for pensions. Mary's ideas about the position of Aboriginal people in Australian society were inclusive and rights-based, and demonstrated her recognition of universal human needs - to raise a family and to find work to support it. She drew on United Nations' conventions such as the International Labour Organisation's 1957 Convention 107 on 'Indigenous and Tribal Populations' pressuring the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement to use this Convention as a basis in planning its 1959 conference. She combined a deep humanity and interest in individuals with a clear-minded recognition of the way such international conventions might be used to shame governments.

See the entry on Barry Christophers for Barry's assessment of the influence of Mary Bennett on members of the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement.

Further reading

Alison Holland, Just Relations: The story of Mary Bennett’s crusade for Aboriginal rights, UWA Publishing, Perth, 2015

Sue Taffe, A White Hot Flame: Mary Montgomerie Bennett, Author, Educator, Activist for Indigenous Justice, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2018

383424

- 391528

- 391534

- 382876

- 383008

- 383424

- 391546

- 382776

- 382880

- 391556

- 391562

- 391568

- 391580

- 391574

- 391586

- 384354

- 383635

- 391596

- 382884

- 383268

- 383959

- 383044

- 391608

- 391614

- 384358

- 383256

- 391624

- 382964

- 391680

- 391686

- 383658

- 382888

- 391696

- 383260

- 382780

- 391706

- 384213

- 383837

- 383264

- 391718

- 383841

- 382968

- 391728

- 383704

- 383012

- 382748

- 382892

- 383570

- 383316

- 391748

- 383048

- 383754

- 383666

- 383104

- 391763

- 383662

- 384061

- 384065

- 391774

- 391780

- 391785

- 383188

- 383708

- 391795

- 391801

- 391807

- 383336

- 384362

- 382856

- 383272

- 383963

- 391819

- 382896

- 391825

- 382972

- 383296

- 383080

- 383758

- 383108

- 384069

- 391851

- 391857

- 391863

- 391869

- 382900

- 384366

- 382784

- 391882

- 391888

- 382904

- 383712

- 391900

- 383084

- 391908