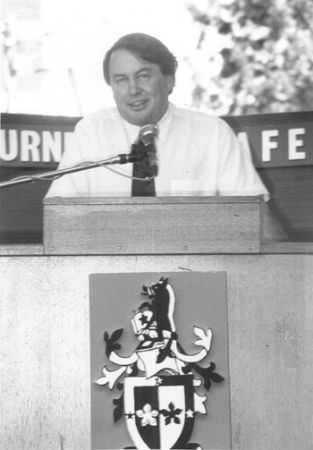

Tom Roper

(1945 to 2023)

Source: Copyright owned by Swinburne University of Technology. Permission for limited re-use is provided under the terms of the Australian Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives (by-nc-nd) licence.

Tom Roper became involved in Student Action for Aborigines in the mid 1960s when the Freedom Ride was being planned as he explained in this extract from an interview in 1997. He joined Abschol when he was a student at the University of Sydney and began work on broadening the perspective, while still continuing to raise funds for scholarships. Along with Tony Lawson, Robert Oke and others, Roper was responsible for Abschol's transformation from a National Union of Australian University students scholarship scheme for Aboriginal students to a well-organised national pressure group.

Well, it really started more with Student Action for Aborigines (SAFA), which was set up, I think, in 1964 by people like Charlie Perkins and others at Sydney University. And I got involved in that. While I wasn't actually on the Freedom Ride (because I needed to stay in Sydney and actually earn money so I could go to university over the next year) I was involved on the outskirts of that, not as a kind of major player. Following that, in the following year, a number of us decided, as well as our involvement in SAFA, we should be involved in the national student organisation, which was Abschol, and we became members of Abschol, and started increasing its involvement, at Sydney initially, and then in the other New South Wales campuses. We in fact set up a New South Wales Abschol organisation. Abschol, traditionally, had been a fairly conservative organisation, mainly concerned with raising funds for scholarships. And I suppose firstly we altered that perspective, while not forgetting the scholarships part, in New South Wales and then that became very much the same nationally. And I was, I suppose you could say, fairly heavily involved in that. By that time we also had very strong support from people in Victoria as well, like Colin Benjamin and Rob Oke and others, to make Abschol a far broader organisation than traditionally it had been.

Sue: So, SAFA, Student Action for Aborigines, do you see that as having been significant in politicising Abschol or getting more students involved?

Tom: Two things: Firstly in highlighting issues of Aboriginal rights which had been discussed but not highlighted, and secondly providing a reason for firstly a significant number of New South Wales students to get involved, but then other students as well. I mean SAFA wasn't just involved in the one Freedom Ride, and that was the end of it. It was also involved in looking at the situation in a number of New South Wales country towns. I can remember two of us going out to Wellington to look at the situation there which was fairly grim, and also being involved in demonstrations in, it must have been the '65 or '66 New South Wales state election, where we mounted a vigil outside both party headquarters for the hundred hours before the election again to generate publicity and attention to what was, at that stage, not occurring in New South Wales.

During Tom's presidency an effective national structure was developed with active committees in all Australian universities. Abschol developed during these years as an organisation committed to improving educational opportunities for Aboriginal students, while taking on a broader political role, such as giving practical and financial support to the Gurindji people in establishing themselves at Wattie Creek.

Well there was a lot of on-campus activity in that one of the things we did that had been going on for some years at Sydney had been the organisation of an annual appeal, the funds from which went into the Scholarship Fund, which was based down in Melbourne, and that occurred right through the country on all of the campuses. And that got a variety of people involved. But as well, because of the activity of SAFA and then of Abschol itself, quite a number of students got involved either in the political or the fundraising or also the tutoring part. We had tutoring schemes being run, based on American models in quite a number of areas, as well using students as volunteer tutors for young Aboriginal people. So there were a variety of roles in which people became involved, and quite significant numbers of people became interested. I can remember having about a thousand students along to a rally, this was a couple years later at the University of Queensland, to hear people discuss the Queensland situation and Queensland legislation. So there was a lot of interest, and there was a general ferment of concern about the state of the world and so it wasn't competition between Vietnam or Aboriginal matters or other issues either. There was a general concern that things needed to be changed.

He rose to the position of National Director of Abschol during a period of great change, from cooperation and consensus marked by the passage of the 1967 Referendum to division and dissent when the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) split in 1970.

Tom: Well I think that FCAATSI was very important in the campaign for the '67 Referendum. And I mean we tend to forget the importance of that. No government has since been able to say 'we don't have responsibilities'. And I can remember even discussions we had at ministerial council meetings, when I was Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, the Commonwealth would say 'well that's a state responsibility' and I was able to say to Gerry [Hand] 'Well that's not why we ran around the country in 1967 so you can say that. The Australian people clearly gave you a responsibility'. So I think that was very important, I think also very important was the encouragement it gave to the commencement of the land rights movement. Also very important, as I mentioned before, was a committee on labour relations activity, which produced very good reports.

Sue: The one Shirley Andrews and Barry Christophers ran?

Tom: Yes. If that kind of material hadn't been produced, a lot of the argument about equal pay, equal wages and equal conditions would never have got off the ground. So there are a variety of ways in which it was important, but the fact that it was also a national conference where people could go and learn how to speak in a kind of turbulent atmosphere didn't do any of the people who were important in the '70s any harm at all.

Sue: It's always occurred to me that in fact that 90.77% of Australians who voted for the referendum, if they'd known perhaps that that was going to lead to the struggle for land rights, would we have had a 90.77% vote?

Tom: There was certainly those who argued against it, but they didn't get an audience. And I think the majority of Australians, despite the best efforts of Pauline Hanson, still do not believe that Aboriginal people have equality in the country. Now all kinds of reasons are given for that, but nonetheless that's a strong belief, and again there is no question that the Commonwealth has the major responsibility. You can argue that the Commonwealth's not doing enough, or you can argue that it's doing too much. But the argument whether the Commonwealth should be involved died in 1967, and that's, I think a lasting tribute to, I mean not just to FCAATSI, but people like those out at the Aborigines Advancement League who worked hard in Victoria, to make that occur, or the people involved in Sydney, or Joe [McGinness] up in the North. I mean, a whole lot of people played a part in that, and played a part in subsequent events as well. The students just kind of came in at a useful time with a few resources.

Sue: And I think this is a difficult question I suppose, but of course that referendum gave the Commonwealth responsibility for making special laws for Aboriginal people, and allowed Aboriginal people to be counted in the census, but what did it really mean, what do you think it really meant? Why did so many people vote 'yes'? Was it just that or was there something underlying that?

Tom: I think the reason it passed so clearly was it seems so ludicrous that the Commonwealth Parliament could pass laws about almost anything, except about Aboriginal people. I mean it didn't give the total control of Aboriginal affairs to the Commonwealth. What it did was allow the Commonwealth to have a say and of course if there is a Commonwealth and a state law, the Commonwealth has precedence, I was very much involved in that. I talked to thousands of people during the course of the first few months of 1967, and you could engage people in discussions, and they would agree that it was crazy that the Commonwealth could pass laws about anyone unless they were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. And I think that was one of the reasons it got such a huge support. Of course it got much more support proportionately in Melbourne than it got on the north coast of New South Wales, where, as we all know, there were some very vigorous racist views. I mean I can remember when the fellow that owned the Bowraville picture theatres said to Charlie Perkins, 'I don't care if you're the Prime Minister of Australia, you're still not sitting in the white seats', or words to that effect.

That was on that Freedom Ride where a number of barriers were broken. You used to come up against those. I can remember being involved - there was a group of students were at a work camp in Port Augusta in South Australia, and I was over there and in fact the Aboriginal person who was the foreman for the students was the one who was making sure the work they did stood up. We all went down to the Port Augusta picture theatre, and we just asked for five or six, or whatever the number of tickets were, and the Aboriginal foreman was told no, that he'd have to sit down the front. And we had an immediate kind of blue, and effectively broke the barrier then and there. I mean that was fairly common in a lot of towns in Australia: like Gnowangerup using its labour market funds to fix the white part up, while the Aboriginal part was terrible. I mean there are still some terrible, absolutely appalling situations, but at least now the argument is about whether the Commonwealth is doing enough not whether it should be doing anything at all.

Tom was interested both in how to provide educational opportunities for Aboriginal students and in the broader political questions of the day. After Labor formed government nationally, he worked as a research officer in Aboriginal education for Gordon Bryant in 1973 and then went on to a career in the Victorian parliament as a Labor MLA. He held portfolios in Aboriginal Affairs and Health.

Tom: It was very much an interim thing. I had been preselected for the seat at Brunswick West [Victorian state seat], and I was actually working as a senior tutor out in the Education Faculty at Latrobe, and Gordon [Bryant] contacted me and asked me if I'd be prepared to work with him and the department [of Aboriginal Affairs]. It was very clear that it was with both, and I said yes, I'd be happy to do that, and I did that, not full time, because I had responsibilities down at Latrobe [University], and also I was running for a seat in Parliament. But I put as much time in it as I could.

Sue: Looks full time when you read the record.

Tom: I got around to a lot. We started, for instance, an Aboriginal education program. For the first time, we got the Commonwealth to actually look at what was occurring and there was a lot occurring in South Australia; there was nothing occurring in New South Wales; very little occurring in Western Australia. We were able, in the space of about six months, to gee up a whole lot of people and programs. We were able to introduce the idea of bilingual education, which I'd seen operating very effectively in the Navaho, on the Navaho reservation, in America a couple of years before. We were able to get rid of the Aboriginal education branch in the Northern Territory. And I've still got the physical education pamphlets of that branch that were being used in 1970-71: things called 'Throw Well' for people learning to throw a javelin, a shot-put; no mention of a boomerang or a spear. And this is in material prepared for and used in the Aboriginal education area in the Northern Territory. We were able to get rid of that. The last thing I was able to do, I had actually already been elected to [Victorian] Parliament but I had to finish off a piece of work. I ran, with the help of the Roberts, a special meeting for Aboriginal elders in the Northern Territory: brought them all in to tell us - and it was a great eye opener for the people who had been running Aboriginal education up there - what they wanted for their children. And one of the things that came up there was the problems that were caused by taking people away from home in the crucial years of their life, to go to places like Kormilda [College in Darwin]. Unfortunately Kormilda had gone too far at that stage to be stopped. It already had all the approvals. But we were able to bring new people and ideas in. I then went into the Victorian Parliament and in fact it was only quite recently I went back to Darwin for the first time since then. But that was a very exciting time in that the administrative structure wasn't there which is the reason that administrative errors occurred.

After leaving politics Tom moved to New York where he worked in environmental policy at all levels. He was a Project Director of the Global Sustainable Energy Islands Initiative.

Source: The extracts on this page are from an interview with Tom Roper conducted by Sue Taffe on 11 November 1996

391857

- 391528

- 391534

- 382876

- 383008

- 383424

- 391546

- 382776

- 382880

- 391556

- 391562

- 391568

- 391580

- 391574

- 391586

- 384354

- 383635

- 391596

- 382884

- 383268

- 383959

- 383044

- 391608

- 391614

- 384358

- 383256

- 391624

- 382964

- 391680

- 391686

- 383658

- 382888

- 391696

- 383260

- 382780

- 391706

- 384213

- 383837

- 383264

- 391718

- 383841

- 382968

- 391728

- 383704

- 383012

- 382748

- 382892

- 383570

- 383316

- 391748

- 383048

- 383754

- 383666

- 383104

- 391763

- 383662

- 384061

- 384065

- 391774

- 391780

- 391785

- 383188

- 383708

- 391795

- 391801

- 391807

- 383336

- 384362

- 382856

- 383272

- 383963

- 391819

- 382896

- 391825

- 382972

- 383296

- 383080

- 383758

- 383108

- 384069

- 391851

- 391857

- 391863

- 391869

- 382900

- 384366

- 382784

- 391882

- 391888

- 382904

- 383712

- 391900

- 383084

- 391908