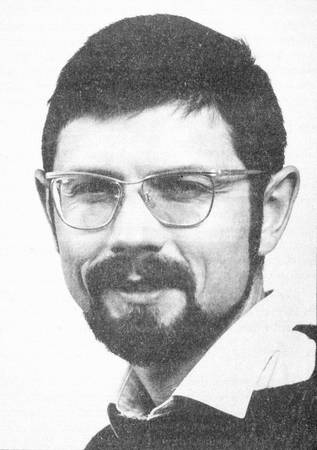

Rodney Hall

(1935)

Source: Faith Bandler, Turning the Tide, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1989

Long before Rodney Hall was known as a successful novelist, he was using his literary skills to let Aboriginal people know about their entitlements to pensions. When amendments to the Social Services Act were implemented in the late 1950s Rod, together with Shirley Andrews, set about ensuring that the people concerned knew what they were entitled to and how to go about getting it. The end result, 'A Yinjilli Leaflet: Social Services for Aborigines' was sent to missions and stations and fringe settlements across Australia.

Meetings with Aboriginal people at places such as Finke River, Hermannsburg and Jay Creek when he was a young man helped Hall to see another world and to consider a people's right to reject assimilation.

We were at the Finke River and two of us had gone walking and we came on a group of people in the Finke River, just sitting in the sand and doing what they were doing, minding their own business. My friend, who was a Russian Australian, and I said 'Sorry, we didn't - we hadn't [realised]' and they didn't speak English, but they were very welcoming and they sat us down. We spent a little while there sitting down and they offered us a cup of tea. They had a camp fire going so we had a cup of tea, and we had a bit of tea, and thanked them very much and off we went. Now, on our way out of that central trip we passed through Jay Creek Mission and you had to have permission - a Church of England mission - and we'd been to Hermannsburg, but Jay Creek refused us permission and we did everything by the book. But we were very short of water, and the leader of the expedition said, 'This is it. We have to go in, irrespective of no permission'. And we drove in that little track. And there were these old people (they all looked old to me then. I was twenty one or twenty two), with pot-bellied kids with berri berri and things that looked like it. I mean, they were in the most shocking condition. And there were mountains, absolutely house-high mountains of rusted, empty baked beans, Heinz baked beans tins. Just, just the most extraordinary sight. And the missionaries were very angry that we'd come in, and ordered us off and it was just like dealing with aggressive police. And by the time I got back to Brisbane, and I had a long session with Kath [Walker] about it, you know: 'I've just - something's got to be done. I know I'm planning to go away next year, and I've got to do that for me, but if there's anything happening I want to be part of it'. Because, you know, putting all the things together I'd seen in the urban people in Brisbane, knowing what her life had been, and then seeing what was happening in the far outback, and that brief experience of being categorically in someone else's country on the Finke River - you know, my mother came from Kangaroo Valley but my parents had been in England and my brother, sister and I were all born over there, and brought back, and told, 'We're coming home. Going home to Brisbane'. But, of course, it was new to us. So I myself had the experience of coming to Australia as a foreign place that I then grew to love, and saw myself as Australian very quickly. And here it was, ten years, eleven years down the track, I'm in a place where, I think, 'No, this is not - this is nothing to do with me. I don't understand this.' I mean, they are profoundly at home here. It made a huge impression.

Rodney Hall met Kath Walker when both attended meetings of the Realist Writers group in Brisbane in the 1950s.

About a year, eighteen months later, the Brisbane Realist Writers Group was founded, and I went. I was the youngest member of that group, and at about the third or fourth meeting Kath Walker turned up. And she was the first Aboriginal person I'd actually met.

Sue: So this is what, '53?

Rodney: This would have been '53 or '54, I can't remember the exact date.

Sue: And it was the Brisbane -?

Rodney: The Brisbane Realist Writers. It would be easy to find out when that was started. And Kath Walker came along, and she was immensely vivacious, and she was terrific, and she had tremendous presence and energy, and we struck a friendship that lasted for life. And partly, I suppose, because I was the youngest member of the group and she was the one that felt, sort of, [the] least self confident about what she was doing, we ended up having coffees together afterwards, after meetings. And then we started seeing each other quite often in the interim. And of course during those meetings, I started to find out about her life and how she'd grown up on Stradbroke Island and how she'd been a domestic in a wealthy and intellectual household in Brisbane, the Cilento household. And she had a certain sort of loyalty to them, which I found outrageous, absolutely outrageous, that she'd been paid this pittance and she said, 'Oh no they looked after me, they did this and did that', you know. And I said, 'No they didn't. They exploited you!' And so we played off each other an awful lot, because I was trying to find out what I wanted to find out. And she was at that stage where she had had her breaks in the army, which was her big break, and then the sporting team itself. But that had all finished and she was looking for what she was going to do. So she was the key figure for me.

... But I think it gave Kath an immense amount of self-confidence, and of course at the FCAATSI [Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders] conference when she read her 'Charter of Aboriginal rights', I mean, which you know, was not really a poem. But as a statement, it was a terrific statement, and people were absolutely bowled over by it ...

And it gave her the build up and the confidence. I mean, somebody will have told the story of her famous riposte to Menzies, when Menzies finally saw her. I mean it took a lot of nerve and also a lot of self confidence to say, 'If you offered me this drink where I come from, you'd be, you could be arrested'. I mean that's plucky stuff and she was always like that. But the poetry gave her something to hold on to. It was like the sport had been; like the army had been. At last she got something else she needed. I mean, Kath was not one of those people - people talk about her as if she was some kind of immensely gifted teacher who began by knowing what to do. She fumbled and made mistakes and voted on the wrong side and struggled to find things. It's to downplay her courage, and her ability to learn by what was happening, to think that she began with it already made. She always needed a kind of, she needed to have something she could do that she centred what she was talking about around, while she found her ideas. She was a very powerful public speaker, partly because she was repetitious, and partly because she had a passionate delivery. But she discovered that. She invented all that. She got it all together, you know, out of courage and thin air. The poetry was very, very important for that. And I had a lot to do with that. I mean, Jim Devaney was the person who encouraged her to put the book together, but I suppose of all the people in Australia, I would have had more to do with the first two books than anybody, because I looked at every poem in every stage of its development.

Rodney Hall was an active member of the Queensland Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. He edited the first national bulletin, 'Yinjilli', for the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement in 1963 and 1964, and convened the Publications Committee in 1963. He speaks here about the Cold War conflicts in Aboriginal organisations in Queensland in the early 1960s.

They called themselves The One People of Australia League [OPAL], of course, and this was roughly speaking a kind of hard line Christian conservative group and Neville Bonner was their, sort of, mainstay person, but didn't do - I mean there were other people, such as Mrs Langford who were the energy behind it. And they got various people interested like Margaret Valadian, I think, at one stage. But their function wasn't to operate as our function was. Their function was to siphon off people and cause divisions and then, when that failed, they actually hired a bus - because we had this silly amateur constitution - and they brought a busload of people who paid their dues at the door and then voted us out of existence and got off with our books and our money and absolutely everything.

Sue: Sorry, voted you out of existence? I'm just not with you there.

Rodney: Well the way meetings can be stacked, you see, it was a -

Sue: So you're talking about the Queensland Council meeting and OPAL came to that?

Rodney: Well they were the OPAL people, but they didn't call themselves OPAL.

Sue: I see. Right.

Rodney: So they just got a whole lot of people who were mainly the kind of - there was a chap called George Cook in Brisbane, who was a kind of Santamaria minor functionary in Brisbane, who had a whole lot of - I'm sure people, in their own terms, had the best of motives. And feeling that they were doing, you know, they were being active anti Communists and that this was a Communist organisation. I'm sure that's what was going on. They got a whole lot of volunteers and they paid their $5 or whatever they had to pay, because our fees were nominal for obvious reasons, and then they voted their own person - I've forgotten his name, something like Creighton, something like that - in as secretary and their own person in as treasurer. And our excellent Chairman, Royce Perkins, he was terrific. He was an insurance person in Brisbane, terrific person Royce Perkins, one of those kind of absolutely incorruptible, clear thinking, slightly narrow [people]. I think he was a sort of Methodist or Presbyterian-type person, but he had a fearless justice for - he was a very quiet man but he was very capable and stood up to fantastic pressure. He was a terrific person, Royce Perkins. But anyway they got rid of everybody else, you see, and then they'd taken over the meeting.

Sue: When was that approximately? I haven't heard that story before.

Rodney: Oh that would have been, the takeover, all Kath's papers would have the exact information about that. I would guess that would have been about August 1961, something like that. That's a real rough guess. Eunice Gilmore is another person who would know exactly.

Eunice was a librarian in the Queensland Public Library. She came from Springsure or somewhere out that way, somewhere in the far country. But as a librarian Eunice has a fantastic store of information. So far as I know she was never connected with FCAATSI, but within the Queensland Council she had a lot of information. Kath Cochrane would know the date of that. Anyway, they took our books and took our money and we just decided (it was at the Friends [Society of Friends] meeting house, ironically) and we just decided that we would go on regardless. I don't think the name [of QCAATSI] had ever been registered, so we just called ourselves the same thing, and met - you know, rang round our own friends and kept meeting. But we had lost all our records and our books. It was a very bitter lesson. So there were lots of complications, and all that stuff was the sort of thing we took to the Federal Council, you know: 'Watch out. This becomes politics, internal as well as external politics'.

He recalls meeting memorable Aboriginal activists at annual FCAATSI conferences.

I remember meeting Mrs Williams and her daughter Winnie Branson from South Australia when Mrs Williams must have been a woman in her late 60s, I suppose, you know, a large, calm, wise sort of person. I thought Mrs Williams was the bees' knees, I was just bowled over by Mrs Williams. And she had set up a co-op on a reserve, and it was a bread co-op, and it was, again, such a lesson in how things can be done. They all bought bread from the local shop in town. They had to get into town and so forth, and somebody in the community or outside the community, somebody had said, 'What if you all, if you bought it yourselves, if someone goes and buys in bulk and you all buy the bread from that someone, that's how you create a pool of money'. And they gave them that little sort of lesson in the origins of a cooperative. And at that stage I was very interested in cooperatives and I'd been reading a lot about them and it really spoke to me. And this wonderful woman [Mrs Williams] has said, 'Yes, yes, we can do this'. So they had a storeroom where their food handouts came from. She secured use of a cupboard in the storeroom and she got her daily supply or every second day of multiple loaves of bread from the same baker, but, because she was buying quantity, she'd got a deduction for it. The baker had brought it out so they didn't have to go to town, so they scored doubly. They got the bread, they sold the bread at a penny more, or whatever, than they actually paid. So it ended up being slightly cheaper for the customer than it had originally been, but there was also created a little pool of communal money. She'd been running this then, I think, for one or two years and she had quite a neat little packet that was the community's money. They were looking at how they were going to expand the co-op to do other things - she and her daughter Winnie Branson, who was then in her 20s or 30s. They were such - Winnie was a cheery, good-time, energetic person and Mrs Williams was this wonderfully serene person of great substance. They were the sort of people I was meeting there.

Rodney Hall was awarded an OAM in 1994.

Source: The extracts on this page are from an interview with Rodney Hall conducted by Sue Taffe on 9 December 1996

383570

- 391528

- 391534

- 382876

- 383008

- 383424

- 391546

- 382776

- 382880

- 391556

- 391562

- 391568

- 391580

- 391574

- 391586

- 384354

- 383635

- 391596

- 382884

- 383268

- 383959

- 383044

- 391608

- 391614

- 384358

- 383256

- 391624

- 382964

- 391680

- 391686

- 383658

- 382888

- 391696

- 383260

- 382780

- 391706

- 384213

- 383837

- 383264

- 391718

- 383841

- 382968

- 391728

- 383704

- 383012

- 382748

- 382892

- 383570

- 383316

- 391748

- 383048

- 383754

- 383666

- 383104

- 391763

- 383662

- 384061

- 384065

- 391774

- 391780

- 391785

- 383188

- 383708

- 391795

- 391801

- 391807

- 383336

- 384362

- 382856

- 383272

- 383963

- 391819

- 382896

- 391825

- 382972

- 383296

- 383080

- 383758

- 383108

- 384069

- 391851

- 391857

- 391863

- 391869

- 382900

- 384366

- 382784

- 391882

- 391888

- 382904

- 383712

- 391900

- 383084

- 391908