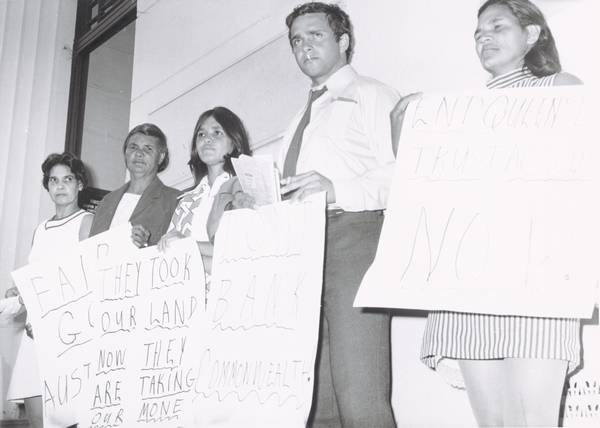

Aboriginal students at the University of New England were particularly active in this campaign.

Source: Barry Christophers papers, MS 7992, National Library of Australia

Aboriginal Queenslanders who were 'under the Act' did not have the right to spend or manage their own money. Their earnings were paid into a trust fund, and doled out to them by the local policeman, as he saw fit. The campaign against the Trust Fund drew attention to this injustice.

Queensland legislation, which limited the rights of Aboriginal people, was the most coercive and intrusive in Australia and had been a focus for activists throughout the 1960s. Three years after the 1967 Referendum which gave the federal government power to make special laws for Indigenous Australians, this situation was unchanged. The federal government had made no attempt to get Queensland to bring its legislation into line with the other states. Queensland activists such as Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal) and Joe McGinness had long been keen to expose the abuses of the Queensland Trust Fund.

Life under the Act

Under the Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act a district officer of the Queensland Department of Aboriginal and Island Affairs could 'undertake and maintain the management of the property of any assisted Aborigine who usually resides within the district of such officer'. The Regulations under this Act spelled out the degree of undemocratic control to which Aboriginal Queenslanders were subjected. There was no trial by jury on reserves. The Director of Native Affairs was the guardian of every Aboriginal child in the state and people could be forcibly moved away from their homes.

Regulations, Aboriginal Preservation and Protection Act 1939 (Qld)

Queensland Government Gazette, 23 April 1945

More info on Regulations, Aboriginal Preservation and Protection Act 1939 (Qld)

This Act was replaced in 1965 with the passage of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Act but most of the controlling detail in the earlier regulations remained. For example, Section 20 of the Act empowered an officer to 'take possession of, retain, sell or otherwise dispose of any such property' if satisfied that 'the best interests of such assisted Aborigines require it'. This absolute power, especially in remote Far North Queensland was open to abuse. [1]

These powers led to charges of forgery, and of lax banking practice such as the failure to record interest payments and even of regular deposits. As well, district officers took it upon themselves to decide whether to allow people to withdraw their earnings and how much they should be allowed to have, as the following memo shows.

Queensland District officers controlled people's access to their bank accounts

Barry Christophers papers, MS 7992, National Library of Australia, Canberra. Reproduced with permission of the Department of Communities, Queensland.

More info on Queensland District officers controlled people's access to their bank accounts

Campaigning against the Trust Fund

The Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advancement League reported in their January 1969 newsletter that they had identified 'discrepancies that would not occur in normal banking practice'. Barry Christophers publicised these abuses and attacked the Act on two fronts - political and legislative.

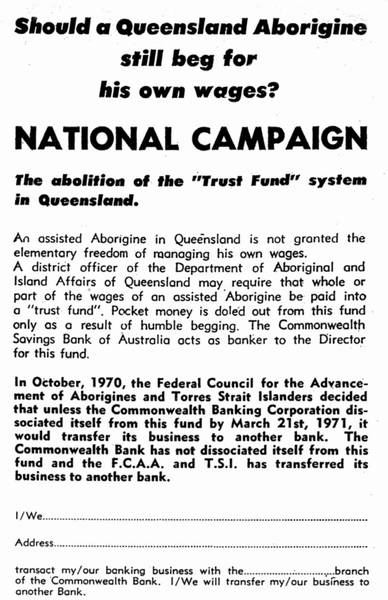

A campaign was launched to alert the public to the situation. 'Should a Queensland Aborigine still beg for his own wages?' asked the advertisement placed in newspapers around the country. The Commonwealth Savings Bank of Australia was the banker for the operation of the Queensland trust fund system. The campaign asked people who had bank accounts with the Commonwealth Bank to close them. Despite a vigorous campaign, however, most people were reluctant to take this action. The boycott strategy failed to persuade supporters, many of whom were reluctant to upset their banking arrangements.

This campaign, against the Queensland Trust Fund, asked people to close their Commonwealth Bank accounts in protest at this bank's management of the Queensland Trust Fund. This petition was placed in major Australian daily newspapers.

Source: Barry Christophers Papers, 1951-1981, MS7992/6/12, National Library of Australia

Taking the Act to court

Fighting the Queensland Act through the courts proved to be more successful when a Mt Isa stockman, John Belia, who had kept a careful record of his pay (despite being unable to read) put himself forward to test the legality of the Act. Garth Nettheim, from the University of New South Wales Law Faculty, and Professor Hal Wootten, President of the newly formed Aboriginal Legal Service in Sydney, advised on the proposed challenge. The case was to dispute the Department of Aboriginal and Islander Affairs' assessment of Belia's classification as 'assisted' and therefore unable to manage his own pay. Activists such as Ruth Kaplan, Joe McGinness and Barry Christophers worked tirelesly on this case for three years.

Finally, in October 1972, the Cloncurry court in north-west Queensland heard the case. John Belia was questioned to determine his ability to recognise the value of different amounts of money. The court found in favour of John Belia. A stockman with four children, Belia had won the right, through the courts, to do what any white Australian worker took for granted: manage his own earnings. [2] This was a small symbolic victory for the lawyers, accountants and black and white activists, led by Christophers, who had been working for two years for this result. It showed that the interpretation of the Queensland law could be challenged. However, it did not change the legislation. The 1965 Act was repealed and replaced in 1971 by the Aborigines Act 1971, which abolished the status of 'assisted Aborigines'.

The struggle continues

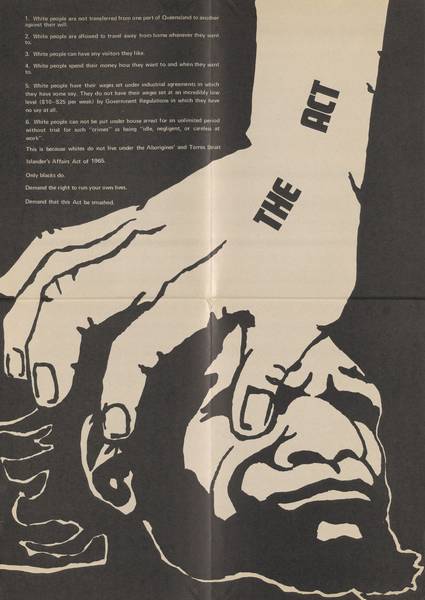

The fight against the Queensland Act continued but with a different focus. Young Aboriginal activists such as Denis Walker, Bruce McGuinness and Gary Foley and Abschol leaders such as Tony Lawson favoured direct action, drawing attention to the civil liberties restrictions experienced by people on Palm Island. The 'Smash the Act' campaign expressed Aboriginal frustration. More than four years after the successful 1967 Referendum, which empowered the Commonwealth in Aboriginal affairs, repressive Queensland laws remained.

'Smash the Act' was the name of the campaign run by Denis Walker and other members of the Queensland Tribal Council.

Source: Barry Christophers papers, National Library of Australia

Since the 1990s the Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research Action (FAIRA) has been lodging claims with the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission for compensation to Aboriginal Queenslanders whose earnings and pensions were withheld through the Trust Fund. Historian Ros Kidd has contributed her research findings on Queensland government abuse of these monies to the battles for restitution. While the Queensland government has made an offer of reparation, the issue has by no means been satisfactorily resolved.

Related resources

Reading

R Kidd, The Way We Civilise, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1997

R Kidd, Black Lives, Government Lies, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2006

R Kidd, Trustees on Trial: Recovering the Stolen Wages, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2006

People

Barry Christophers

Gary Foley

Bruce McGuinness

Joe McGinness

Denis Walker

Kath Walker