Confrontation

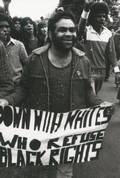

As tension mounted between Tent Embassy protesters and the government, Abschol organised a national moratorium for 'Black Rights' for 14 July, National Aborigines Day 1972. Work stoppages and marches took place in capital cities. Trade unions placed a large advertisement in The Australian, in which they reminded readers of the 1971 Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) decision asking for the restoration of 'tribal land rights' and for the recognition of 'Aboriginal people as distinct, viable national minorities entitled to special facilities for continued self development'. [1]

Trade unions declaration in support of Aboriginal civil and land rights

The Australian, 14 July 1972

More info on Trade unions declaration in support of Aboriginal civil and land rights

By this day, when the tents were forcibly removed, there were hundreds of people protesting at the government's failure to address the issue of Aboriginal land rights.

Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia

On Thursday 20 July 1972, a police force of 150 marched towards the Embassy. The supporters linked arms around the tents and sang 'We Shall Not Be Moved'. A brawl, leading to a number of arrests, was captured by the television cameras for the evening news. The tents were torn down.

On this day the police, ordered to remove the tents, clashed violently with the protestors.

Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia

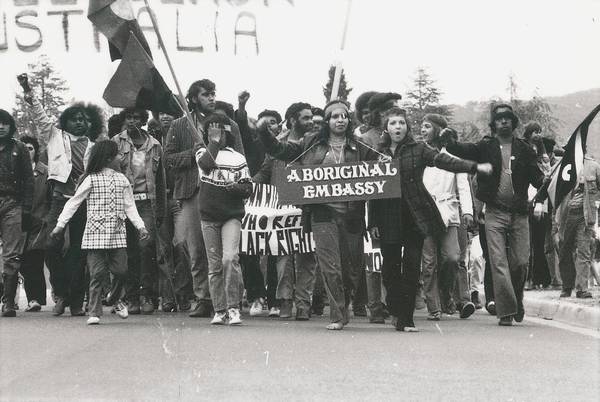

Marchers outside Parliament House, 30 July 1972

Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia

More info on Marchers outside Parliament House, 30 July 1972

The following Sunday, when supporters numbered around 200, the tents were re-erected. Further violent confrontation between the 360-strong police force and the protestors took place. The Embassy tents were pulled down for the second time.

By Monday 31 July, over 2000 people were gathered on the lawns opposite Parliament House . 'I never saw so many people [in one place] in all my life,' recalled Aboriginal activist Michael Anderson.

By 30 July 1972 there were 2000 demonstrators on the lawns opposite Parliament House.

Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia

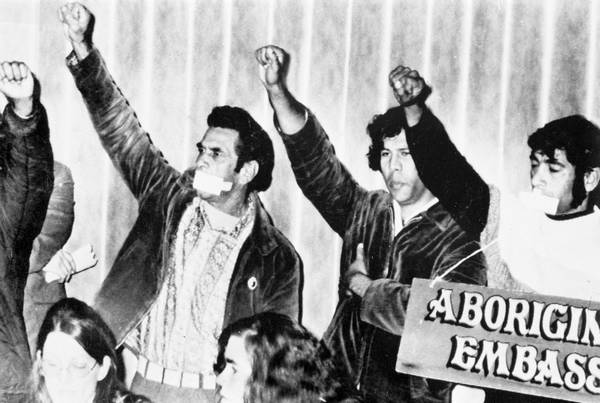

The tents were peacefully re-erected and just as peacefully removed by the protestors themselves, bringing to an end this powerfully visual expression of frustration over the government's failure to recognise and act on the call to legislate for an Aboriginal right to land. Ministers Hunt and Howson agreed to talk to the protesters, but Chicka Dixon, Paul Coe and Robert McLeod did not believe the offer was sincere.

The gag on Dixon and McLeod refers to Minister Howson's refusal to speak to Embassy spokespeople, asserting that they did not represent Aboriginal people.

Source: Audio Visual Archive, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra. Permission Chicka Dixon

Images of police violence against young women and men were on the front pages of the daily newspapers as well as on the evening television news.

With the passage of new legislation specifically to remove the Aboriginal Embassy, the police were ordered to pull down the tents.

Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia

People were outraged at the government's inept and disdainful handling of the affair. Hundreds wrote to Prime Minister McMahon telling him of their voting intentions in the coming election.

This was not the end of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. Aboriginal activists questioned the legality of the ordinance which allowed the police to tear the tents down. Justice Blackburn found that the ordinance had not been notified according to the provisions of the Act. Both Houses of Parliament debated the government's clumsy handling of the Aboriginal Embassy and a former government minister, Jim Killen, crossed the floor to vote with the Opposition over the re-gazettal of the ordinance. The tents were again erected and removed by the protesters themselves, for the fourth time.

Unlike earlier campaigns, the Tent Embassy campaign was initiated and carried forward by Indigenous activists themselves. For Shirley (Mum Shirl) Smith, it was the beginning of a 'whole new road ... learning about politics'. [2] She was not alone.

Related resources

384472

- 384334

- 384370

- 384400

- 384409

- 384472

- 384481