The number of tents grew during the first half of 1972. As this photo indicates the protestors were full time residents.

Source: A7973, INT1205/1, National Archives of Australia, Canberra

When Parliament resumed in mid February 1972, there were 11 tents on the lawns opposite Parliament House. Leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam, accepted an invitation from Embassy organisers to visit the tents and speak with representatives. This gave it further recognition and legitimacy.

Aboriginal journalist and activist John Newfong explained the purpose of the Embassy in an article in Identity.

'The Aboriginal Embassy: its purpose and aims', John Newfong

Identity, July 1972

Download 'The Aboriginal Embassy: its purpose and aims', John Newfong [PDF 2788kb]

Dr HC Coombs, chairman of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, also accepted an invitation to speak with Embassy protestors.

In March 1972, Embassy leaders addressed 200 Australian National University students, asking for their support for the protest. Canberra university students billeted Aboriginal protestors, joined the crowd on the lawns, and opened a bank account for the Embassy through the Student Representative Council. [1] Law students were invited to examine the legal position of the Embassy.

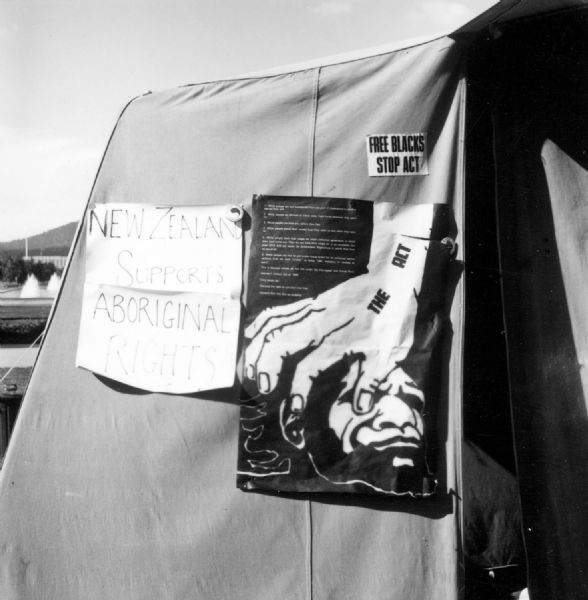

Overseas visitors to the national capital, such as members of the Canadian Indian Claims Commission, visited the Aboriginal Embassy, as did Soviet diplomats and an Irish Republican Army member.

This tent carries a poster which offers New Zealand support. Another message shows the Queensland Aborigines Act as a hand crushing an Aboriginal Queenslander.

Source: A7973/1, INT1205/4, National Archives of Australia, Canberra

All the while, an increasing number of Aboriginal people from all over the country were camped on the lawns opposite Parliament House.

The land opposite Parliament House quickly became the site of numerous tents following the original beach umbrella of 26 January.

Source: A7973, INT1205/3, National Archives of Australia, Canberra

From January to July the number of tents and permanent protestors grew.

Source: A7973, INT1205/6, National Archives of Australia, Canberra

Related resources

People

Organisation

Council for Aboriginal Affairs

Footnotes

1 Scott Robinson, 'The Aboriginal Tent Embassy, 1972', MA thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, 1993, pp. 120-122.

384400

- 384334

- 384370

- 384400

- 384409

- 384472

- 384481