Australia in the 1950s

Note on the content of this page

This content was specifically developed to complement a stand-alone unit of work for students. It summarises content about the Warburton Ranges and Social Services found elsewhere on the site. If you are not a student working on the 1967 Referendum, you may wish to skip to Early petitions.

Two worlds

Australia in the immediate post-war period consisted of two separate worlds. The vast majority of its people lived in a world of houses serviced with water and power, where laws ensured social order, where people on the whole had jobs to do and enough to eat and, if they didn't, the state helped them through hard times. Most people lived in or near cities. They were proud to be subjects of the Queen and believed that they lived in a fair and just democracy, unhindered by problems such as class distinctions in Britain, or racial tensions in the United States or South Africa.

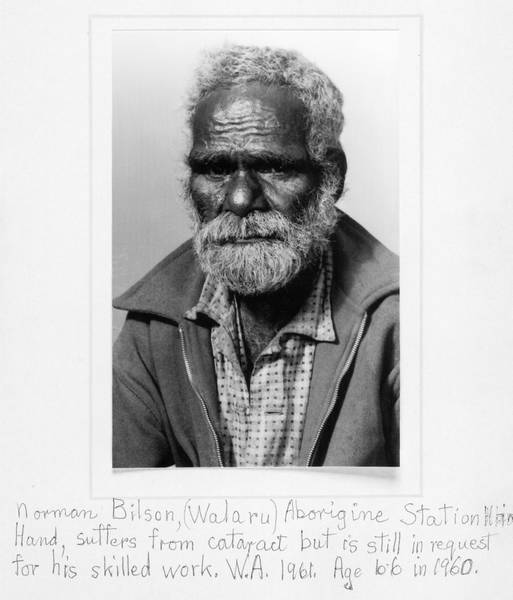

The other world was inhabited by people whose ancestors had lived here for many generations - the Indigenous Australians. By the 1950s most had lost their lands and lived in poverty on the fringes of non-Indigenous society. Many were not eligible for the dole or other state or federal benefits which non-Indigenous people received. State laws controlled where many Indigenous people could live, where they could or couldn't move and whom they could marry. Many Indigenous Australians were not legal guardians of their own children and were not permitted to manage their own earnings. Norman Bilson (pictured below) had to fight to receive the old age pension. For more on his struggle see Social Service benefits.

Written on the image by Mary Bennett: 'Norman Bilson, (Walaru), Aborigine Station Hand, suffers from cataract but is still in request for his skilled work. W.A. 1961. Age 66 in 1960.'

Source: Box 12/6, Council for Aboriginal Rights (Vic.) Papers, MS 12913, State Library of Victoria

There was little contact between the inhabitants of these two worlds and the majority were ignorant of or indifferent to the difficulties faced by Indigenous Australians. Some, who were both aware of Indigenous disadvantage and doing what they could to address it, recognised the possibilities of a grass-roots reform movement to bring the rights and protections of Australian citizenship to all Australians.

The catalyst for change

Early in 1957 news of a report by the Western Australian government provided the catalyst for a reform movement. It drew attention to the plight of Aboriginal people still living traditionally in the central Australian desert. According to this report, malnutrition, blindness and disease were all commonplace among the Aboriginal people of the Warburton Ranges region.

Report of Conditions at Laverton and Warburton Ranges, December 1956

Source: A452, 1957/245, National Archives of Australia, Canberra

More info on Report of Conditions at Laverton and Warburton Ranges, December 1956

The Report of the Select Committee appointed to 'Enquire into Native Welfare Conditions in the Laverton-Warburton Ranges area' (known as the Grayden Report after its principal author Bill Grayden, MLA) argued that the extreme conditions under which these people lived was made worse due to the use of their lands by the Australian-British atomic testing program.

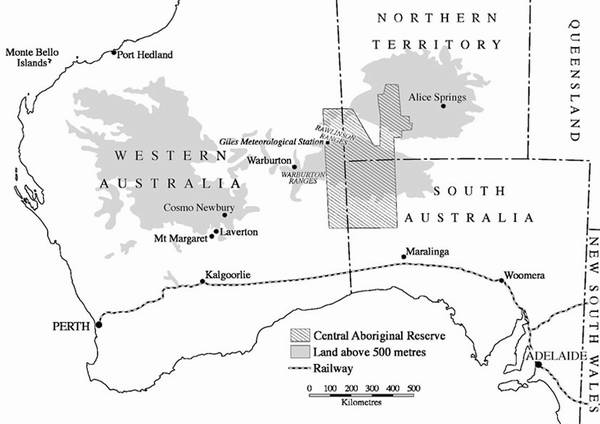

Rockets were launched at the Woomera Rocket Range in a north-westerly direction towards the Monte Bello Islands.

Source: Drawn by Gary Swinton, Monash University

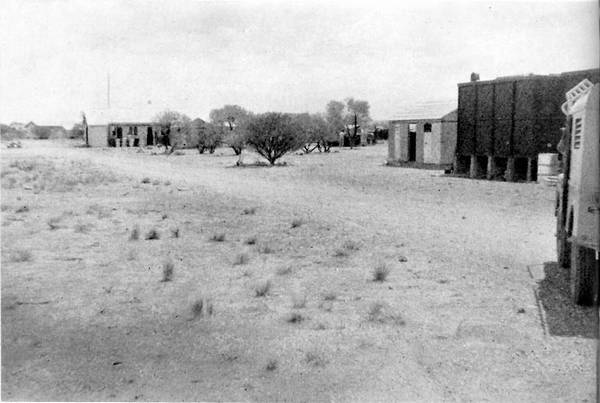

In addition, a natural oasis at Sladen Waters was chosen as the place for a weather station to support the rocket-launching program, upsetting the natural rhythm of hunter and hunted. Although the Commonwealth program was having a negative impact on the people living difficult lives on the reserve, Aboriginal affairs were a state responsibility - in this case the Western Australian government. For a more detailed account, see Warburton Ranges controversy.

This weather station was built in the Central Aboriginal Reserve to support the British/Australian joint weapons testing program. It was established to gather data on wind and weather prior to rocket launching and it inevitably had an effect on the nomadic peoples living in this region. Source: William Grayden, Adam and Atoms, Daniels, Perth, 1957

Grassroots organisations form

A film covering these events (later called Manslaughter when it was shown on television) was made to provide evidence of the suffering of the Aboriginal people to a horrified Australian public. It was shown in local halls and community centres across the country. From the community outrage generated by this film the Victorian Aborigines Advancement League (VAAL) was formed in 1957 with the purpose of working towards the achievement of full citizens' rights for Aboriginal people throughout the Commonwealth. Doug Nicholls, who had met with and provided temporary food relief for an Aboriginal group still living traditionally, vowed to work for Aboriginal people across Australia. He became a Field Officer with VAAL.

Nicholls was a member of an expedition to the Warburton Ranges which came across some severely malnourished groups with some people too weak to keep up with the group.

Source: William Grayden, Adam and Atoms, Daniels, Perth, 19577

In 1958 VAAL joined forces with eight other similar bodies to form the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA). The goal of FCAA was the achievement of 'equal citizens' rights' for Aboriginal Australians. One of its strategies for attaining citizens rights was the amendment of the Australian Constitution to give the Commonwealth government power to legislate for Aboriginal people.

Twenty-six people attended this meeting, which formed the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement, including the three Aboriginal delegates and Bill Onus, an Aboriginal observer, representing the Australian Aborigines' League.

Source: The Advertiser, Adelaide, 17 February 1958

382988

- 382980

- 382988

- 383016

- 383052

- 383092

- 383112

- 383128

- 383200

- 383216

- 383280