The argument for citizenship as a right

Unlike Paul Hasluck, who considered that Aboriginal Australians had to earn citizenship (though this wasn't the case for non-Aboriginal Australians), the people who had formed the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA) saw citizenship as a right. They drew on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted and proclaimed by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948, which set out the rights that should apply to all human beings regardless of their circumstances. This document, to which Australia was a signatory, would become a benchmark against which FCAA civil rights activists would measure abuses of Aboriginal human rights. [1]

In 1959, Gordon Bryant, vice-president of FCAA and the federal Labor member for Wills, asked Attorney-General Garfield Barwick to clarify exactly what was meant by the term 'citizenship' when applied to Aboriginal Australians.

In reply, Barwick explained that Aboriginal people were Australian citizens under the Nationality and Citizenship Act, but that any limitations to their rights as citizens came from laws passed by state legislatures. [2]

In 1958, Mary Bennett, a Western Australian activist who was both attuned to the needs of her impoverished Kalgoorlie Aboriginal neighbours and aware of moves within the international community to safeguard the rights of colonised peoples, drew attention to International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 107 concerning 'the protection of indigenous and other tribal and semi-tribal populations in independent countries'. Whereas the Declaration of Human Rights emphasised the universal rights of all people, the ILO Convention looked specifically at the rights of Indigenous peoples who had been colonised. It sought to secure for Indigenous populations the same legal protections offered to the rest of the community.

International Labour Organization Convention 107

United Nations Association of Australia, 1957

Download International Labour Organization Convention 107 [PDF 2279kb]

While the basic focus of Convention 107 was on equal rights and integration, it went further, stating:

The right of ownership, collective or individual, of the members of the populations concerned over the lands which these populations traditionally occupy shall be recognised.

Australia, however, did not sign the convention.

The agenda of the second annual conference of FCAA, which was held in Melbourne in 1959, was shaped according to the articles of Convention 107 as a way of alerting other activists of this international convention and its relevance to Australia. One conclusion they came to was that the Australian Constitution needed to be changed so that the Commonwealth government could take a more active role and responsibility. Another was to continue to publicise cases of injustice.

The FCAA showed that it was prepared to challenge both law makers and law enforcers, such as mission superintendents and clerks of petty sessions. In remote parts of the country the police officer often had the additional titles of local Protector of Aborigines and the Clerk of Petty Sessions as well as being under sometimes intense pressure to support pastoralists in conflicts with local Aborigines. 'Theoretical' citizenship rights meant next to nothing in a conflict which saw the rights of pastoralists to protection of their property - cattle - overriding the rights of a people to their hunting land. Social Darwinism provided a rationale for dispossession, retaliation after cattle theft, and the use of leg irons. Social Darwinists argued that the Aboriginal race was genetically inferior to Europeans and therefore less fit in the battle for survival.

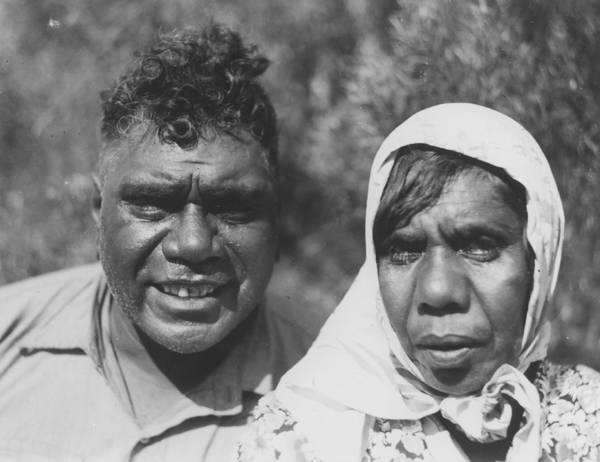

Source: National Library of Australia

Related resources

People

Mary Bennett

Gordon Bryant

Paul Hasluck

Organisation

Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement

Footnotes

1 See the full text of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights on the United Nations website. (This link opens in a new window.)

2 See the full text of the Nationality and Citizenship Act on the Documenting a Democracy website hosted by the National Archives of Australia. (This link opens in a new window.)